There’s a bit of legend around cutthroat trout.

Most people think of cutthroat trout as a Rocky Mountain fish common to mountain lakes beneath glacial cirques, or a small stream fish living among boulders, or a big water fish in places like the Yellowstone. But if you’re talking about populations of cutthroat that migrate in hundreds of rivers, with dozens of spawning populations and numerous individuals growing to 16, 20 even 24 inches in size you’re only talking about one place: tidewater in the Pacific Northwest.

Coastal cutthroat, or sea-run cutthroat, swim in water from Prince William Sound in Alaska south to California’s Eel River and one of their traditional sanctuaries has been the protected tidewater of Puget Sound. Four million humans have also come to enjoy the protected tidewater environment of Puget Sound and their numbers are growing by about 60,000 annually. All those people have changed the coastal environment for cutthroat and about five years ago fly fishers began to ask whether coastal cutthroat were being crowded out of their native habitat. Problem was, nobody knew, because few scientists had studied coastal cutthroat relative to their larger salmon cousins.

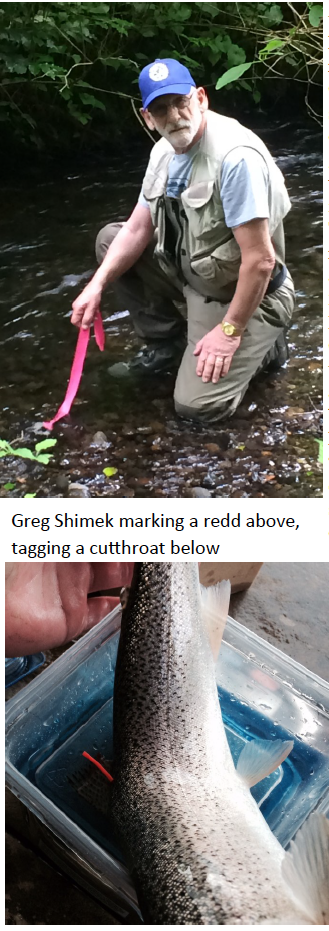

Fish biologists have reams of data on Chinook and coho salmon because they are the cash crops of Northwest waters. And since 1999 it hasn’t been legal to harvest cutthroat in saltwater so consumptive sportsmen have focused elsewhere. There was virtually nothing known about the health of coastal cutthroat until a fly fisher named Greg Shimek and some friends started pushing for answers about 5 years ago.

“We were a few dedicated conservationists who wanted to find out more about Washington’s true native trout,” said Shimek.

About the same time Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife biologist James Losee was “putting together some low budget studies focused on cutthroat spawning.” They joined forces. Shimek and his partners walked the streams and counted redds. Losee guided the work and compiled the data. The result was the first-ever study of coastal cutthroat spawning behavior published in 2016 in the American Journal of Fisheries Management.

“It surprised us that nothing on this topic had never been published before,” said Losee.

Coalition

given the 2019

Bill Mackay

Conservation

Award

Today, Shimek is the leading voice for what has become the Coastal Cutthroat Coalition, which raises awareness of the cutthroat’s place in the Sound and raises funding for Losee’s research to understand the fish, its habitat and our impact on its aquatic home. The Washington Council of FFI has donated to the Coalition’s work and this year the Council presented Shimek and the Coalition the Washington Council’s Bill Mackay Conservation at the Council Fair in May.

Today, Shimek is the leading voice for what has become the Coastal Cutthroat Coalition, which raises awareness of the cutthroat’s place in the Sound and raises funding for Losee’s research to understand the fish, its habitat and our impact on its aquatic home. The Washington Council of FFI has donated to the Coalition’s work and this year the Council presented Shimek and the Coalition the Washington Council’s Bill Mackay Conservation at the Council Fair in May.

In its first four years, the Coalition has published several studies from cataloging spawning streams to ground-breaking research on cutthroat spawning timing, how redds are impacted by variation in water supply, migration patterns and cutthroat behavior in saltwater.

“In the South Sound we discovered that each stream has its own genetic profile,” said Shimek. There is less interbreeding between streams than thought, he said, and it also means each stream harbors fish that give coastal cutthroat more genetic variety. The Coalition is at work on a separate study of 17 streams in Hood Canal to find if the same is true of that habitat as well.